CLEOPATRA

Michel Auder

Michel Auder

CLEOPATRA

Michel Auder

Opening on February 27, 6 to 8 pm

February 27–April 13, 2025

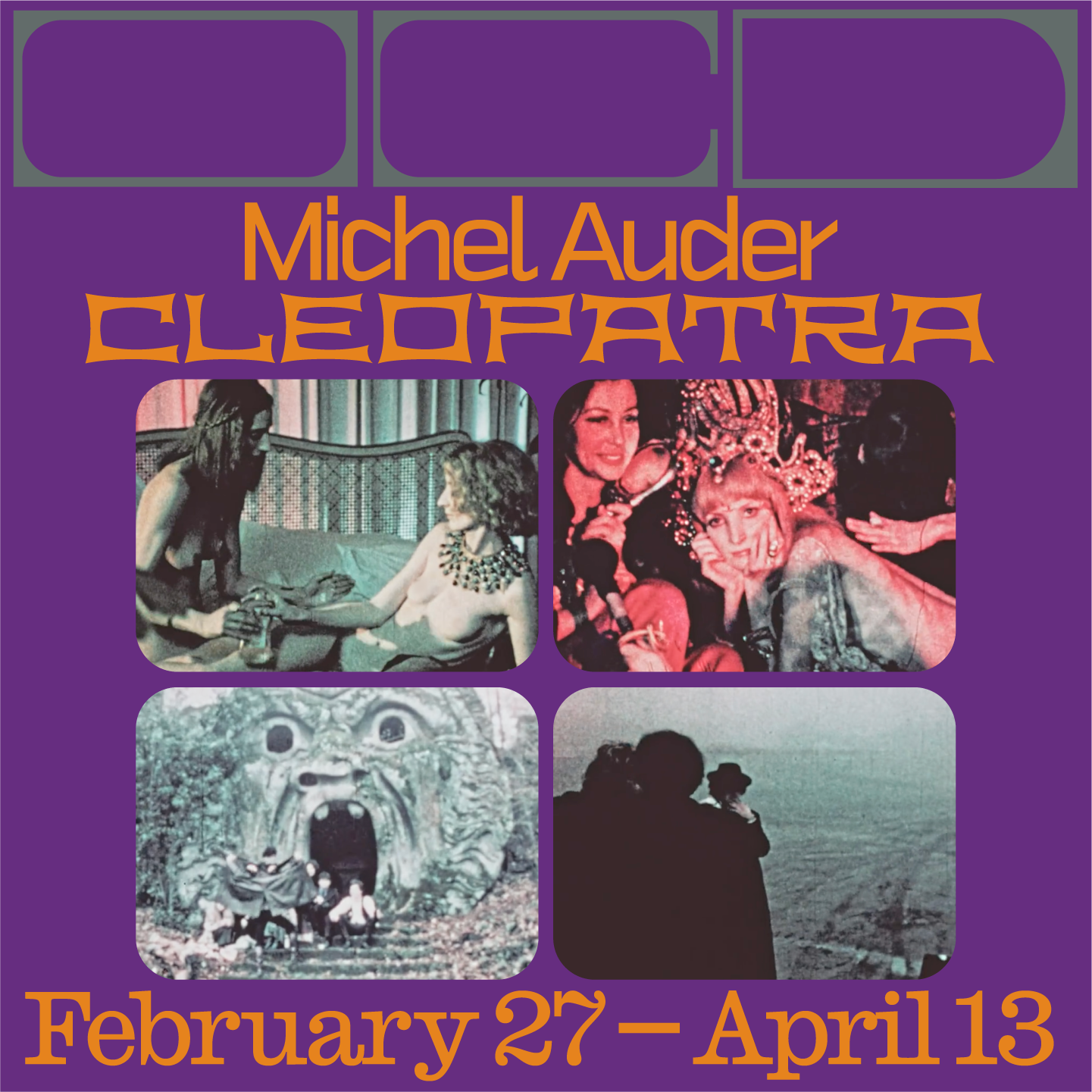

OCDChinatown is pleased to present Cleopatra (1970, 126 mins.), Michel Auder’s early foray into feature films, which stands as an iconoclastic gesture against dogmatic systems of cinema and its genres.

Born in the French manufacturing town of Soissons, northeast of Paris, Auder moved to the capital as a teenager. In 1962, he was drafted into the army and sent to Algeria. “It awakened my political instinct,” he would say years later, transforming him into “a raving leftist.” When May ’68 happened, however, he declined to climb the barricades: “I decided to be political in myself, in the way I conducted my life.” He proceeded from fashion photography to film and worked with the Zanzibar Group, an experimental film collective. But by the end of the decade, Auder had moved to New York. He hung out with Warhol’s Factory personalities and married Warhol’s muse, Viva.

That Warholian aura soon convinced producers to invest in Auder’s next film project, to the tune of $200,000 (equal to over $1.5 million today). The artist set off upstate with some of his closest friends (many of whom happened to be Factory actors), and a loose concept: to remake the 1963 Hollywood epic Cleopatra and tests cinema’s most lofty claim—the promise of the moving image as a medium that manipulates time and desire.

What do you get if you take away Oscar-winning sets and costumes, replace Hollywood stars with Warhol superstars, and jettison any thought of a screenplay? In Auder’s film, snow stands in for desert sand, and the performers often wear nothing more than costume jewelry. A regal-looking Viva is an affectless Cleopatra, a long-haired Louis Waldon plays a virile “Ceasar,” and a bleary-eyed Taylor Mead appears as a floppy minister to the Egyptian queen. Intertitles appear throughout the unruly, fully improvised plot, where actors, always in control of their presence on screen, engage in bucolic anti-authoritarian acts— through a dance, a performance of an orgy, skinny-dipping, and a Roman gladiator-style wrestling match.

Throughout his career, Auder has always complicated, and at times mocked, the fragile boundaries between truth and personal mythmaking, intimacy and spectacle, cinéma vérité and documentary. The artist himself appears alongside his actors in a scene at the airport, as they prepare to fly to Rome—where they filmed at the legendary studio Cinecittá as well as in the city’s outskirts, including the Garden of Monsters in Sacro Bosco di Bomarzo. In the words of one amateur reviewer, Cleopatra seems to be simultaneously “both a feature and the ‘making of.’” The film screened at Cannes, but alas, the producers were appalled and destroyed the negative. Cleopatra was believed lost for many years, until a third-generation copy, made by Jonas Mekas, was found on a shelf at Anthology Film Archives.

Today, Auder’s work chimes with that of a new generation that has exhibited at OCDChinatown — young queer artists who document their intimate lives and relationships as a radical act of creative autonomy.

Michel Auder is represented by Martos Gallery in New York and Karma International in Zurich.

Michel Auder

Opening on February 27, 6 to 8 pm

February 27–April 13, 2025

OCDChinatown is pleased to present Cleopatra (1970, 126 mins.), Michel Auder’s early foray into feature films, which stands as an iconoclastic gesture against dogmatic systems of cinema and its genres.

Born in the French manufacturing town of Soissons, northeast of Paris, Auder moved to the capital as a teenager. In 1962, he was drafted into the army and sent to Algeria. “It awakened my political instinct,” he would say years later, transforming him into “a raving leftist.” When May ’68 happened, however, he declined to climb the barricades: “I decided to be political in myself, in the way I conducted my life.” He proceeded from fashion photography to film and worked with the Zanzibar Group, an experimental film collective. But by the end of the decade, Auder had moved to New York. He hung out with Warhol’s Factory personalities and married Warhol’s muse, Viva.

That Warholian aura soon convinced producers to invest in Auder’s next film project, to the tune of $200,000 (equal to over $1.5 million today). The artist set off upstate with some of his closest friends (many of whom happened to be Factory actors), and a loose concept: to remake the 1963 Hollywood epic Cleopatra and tests cinema’s most lofty claim—the promise of the moving image as a medium that manipulates time and desire.

What do you get if you take away Oscar-winning sets and costumes, replace Hollywood stars with Warhol superstars, and jettison any thought of a screenplay? In Auder’s film, snow stands in for desert sand, and the performers often wear nothing more than costume jewelry. A regal-looking Viva is an affectless Cleopatra, a long-haired Louis Waldon plays a virile “Ceasar,” and a bleary-eyed Taylor Mead appears as a floppy minister to the Egyptian queen. Intertitles appear throughout the unruly, fully improvised plot, where actors, always in control of their presence on screen, engage in bucolic anti-authoritarian acts— through a dance, a performance of an orgy, skinny-dipping, and a Roman gladiator-style wrestling match.

Throughout his career, Auder has always complicated, and at times mocked, the fragile boundaries between truth and personal mythmaking, intimacy and spectacle, cinéma vérité and documentary. The artist himself appears alongside his actors in a scene at the airport, as they prepare to fly to Rome—where they filmed at the legendary studio Cinecittá as well as in the city’s outskirts, including the Garden of Monsters in Sacro Bosco di Bomarzo. In the words of one amateur reviewer, Cleopatra seems to be simultaneously “both a feature and the ‘making of.’” The film screened at Cannes, but alas, the producers were appalled and destroyed the negative. Cleopatra was believed lost for many years, until a third-generation copy, made by Jonas Mekas, was found on a shelf at Anthology Film Archives.

Today, Auder’s work chimes with that of a new generation that has exhibited at OCDChinatown — young queer artists who document their intimate lives and relationships as a radical act of creative autonomy.

Michel Auder is represented by Martos Gallery in New York and Karma International in Zurich.